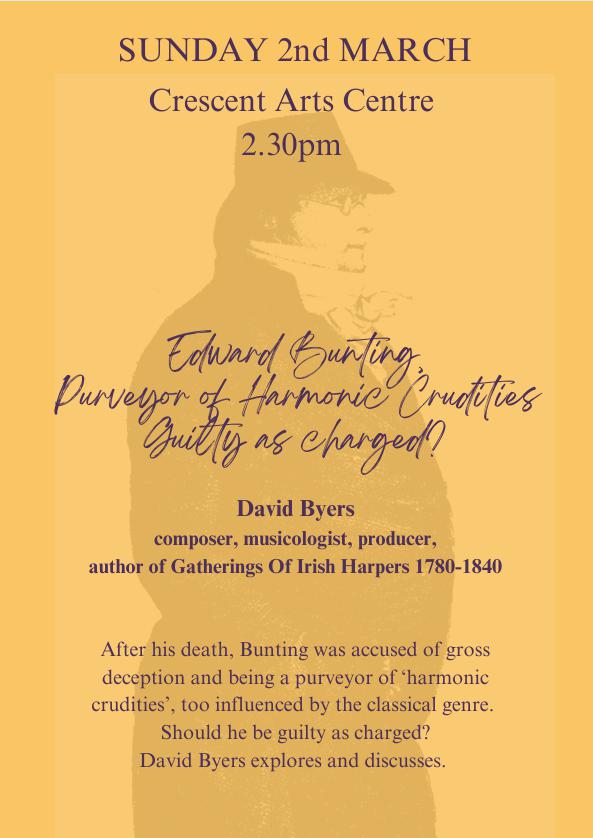

A portrait of Edward Bunting (1773-1843)

compiled by David Byers

"Yes, the time will come when we shall be a great, because a united, nation; and when, glorying in our ancient music, the common property of all, we shall raise a well earned monument to Edward Bunting."

(from a review, most likely by George Petrie, of Ancient Music of Ireland in the Dublin University Magazine, January 1841.)

(from a review, most likely by George Petrie, of Ancient Music of Ireland in the Dublin University Magazine, January 1841.)

Edward Bunting set about publishing his 'General Collection' of some of the treasures of Irish traditional music at the

end of the 18th century. But he certainly wasn't the first.

Some 70 years earlier, John and William Neal published A colection [sic] of the most celebrated Irish tunes proper for the violin, German flute or hautboy

(Dublin 1724).

The only surviving copy (now in the library of The Queen's University, Belfast) had been owned by Bunting and may have inspired him in his endeavours.

Like Bunting's publications, the Neal Collection also seems to have been sourced from the playing of harpers. But Bunting reckoned his collection was the best to date.

The only surviving copy (now in the library of The Queen's University, Belfast) had been owned by Bunting and may have inspired him in his endeavours.

Like Bunting's publications, the Neal Collection also seems to have been sourced from the playing of harpers. But Bunting reckoned his collection was the best to date.

Right: Title page of Bunting's copy of the Neal Collection.

A facsimile reprint edition (2012) by Nicholas Carolan, Treasa Harkin and Jackie Small is available from the Irish Traditional Music Archive shop.

Edward Bunting:

"Before this time there had been but three attempts of this nature. One by Burke Thumoth in 1720 [actually in the 1740s], another by Neill [sic] of Christ Churchyard soon after, and a third by Carolan's son, patronised by Dean Delaney about 1747. In all these the arrangement was calculated rather for the flute or violin than for a keyed instrument, so that the tunes were to a great extent deprived of their peculiar character, and as they were deficient in arrangement, so were they meagre in extent."

"On the whole, the Editor may safely say that his publication ... was the first and only collection of genuine Irish harp music given to the world up to the year 1796."

"On the whole, the Editor may safely say that his publication ... was the first and only collection of genuine Irish harp music given to the world up to the year 1796."

Bunting's piano arrangements of the airs, which he heard played by the last of the Irish harpers, were published, as he stated, in 1796, 1809 (reprinted 1811) and 1840. Dr Peter Downey has recently demonstrated that 1796 was a mis-remembrance. Bunting actually registered his first published volume in Stationers’ Hall in October 1797, having previously registered a much shorter unpublished draft version in May 1796 (Peter Downey, Edward Bunting and the Ancient Irish Music: The Publication History ... Lisburn, 2017) .

The importance of these collections was recognised by a facsimile one-volume reprint published by Waltons of Dublin in 1969. Alas, when Bunting died, one or two-line death notices apart, there was not even one paragraph's tribute in either the Belfast or Dublin press.

Edward Bunting:

The importance of these collections was recognised by a facsimile one-volume reprint published by Waltons of Dublin in 1969. Alas, when Bunting died, one or two-line death notices apart, there was not even one paragraph's tribute in either the Belfast or Dublin press.

Edward Bunting:

"I admit that by reviving Ireland's national music, by making the study and preservation of our Irish melodies the main business of my life, I hope that in years to come I may be thought of as ranking with those worthy Irishmen whose labours have from time to time sustained the reputation of the country for a native literature."

"But above all, the thing which has kept me going is my obsession: a strong innate love of these delightful strains for their own sake. Neither the experience of the best music of other countries nor the control of a vitiated public taste, nor the influence of my advancing years has ever been able to alter or diminish that love."

"But above all, the thing which has kept me going is my obsession: a strong innate love of these delightful strains for their own sake. Neither the experience of the best music of other countries nor the control of a vitiated public taste, nor the influence of my advancing years has ever been able to alter or diminish that love."

Bunting's father, from Derbyshire, moved to Co. Tyrone to work at the relatively new 'coal-works' at Coalisland around 1754. He's believed to have been a manager, probably at the Drumglass pit, but when the mine ran into financial difficulties and closed, Bunting senior moved to Armagh, possibly around 1760. Interestingly, the Coalisland mining venture was owned by a partnership which included the Archbishop of Armagh.

Edward Bunting's

mother was Mary Quin (or Mary O'Quin, according to Belfast historian George Benn in 1880), said to be descended from the chief of an ancient Irish clan, and it was to her that Bunting attributed his musical talents.

In the journal Dúiche Néill, Vol.24 (2017), Frank Bunting, a descendant of Edward Bunting’s elder brother Anthony, points to the surviving List of the Inhabitants of the Town of Armagh, 1770, for evidence of the Buntings in Armagh.

In that Armagh listing is a Bunton [sic] family - Bunton was a frequent misspelling or misinterpretation of Bunting, even well into the 19th century. The family lived in Scotch Street. Edward Bunton (or Bunting) was head of the family. He was a carpenter, perhaps a likely occupation for someone formerly involved with mining. There were five children at that time and the family was Church of Ireland.

In that Armagh listing is a Bunton [sic] family - Bunton was a frequent misspelling or misinterpretation of Bunting, even well into the 19th century. The family lived in Scotch Street. Edward Bunton (or Bunting) was head of the family. He was a carpenter, perhaps a likely occupation for someone formerly involved with mining. There were five children at that time and the family was Church of Ireland.

Child mortality rates were high, but we confidently know of three surviving sons of the marriage: Anthony, Edward and John were all born in Armagh and destined to become organists and teachers.

According to George Petrie (of whom more below), Edward was the youngest, though the details on John's gravestone (maybe not always to be trusted) suggest that he was the youngest (1776-1828). Edward was born in February 1773.

It seems most likely that Anthony and Edward (and maybe John if he's older than his gravestone suggests) would have had lessons from Robert Barnes who was Armagh Cathedral organist between 1759 and 1774.

After 1774, Barnes was 'reassigned' to the role of Vicar Choral, due to his 'insufficiencies' as an organist! His successor on the fine c.1765 organ by John Snetzler, Dr Langrish Doyle (organist from 1776 to 1780), may also have given the Bunting boys some tuition.

Tragedy struck with the death of the boys' father around 1782.

Anthony (1765-1851) by then was organist of St Peter's Church in Drogheda. The church organ, installed in 1771, had also been built by John Snetzler in London, and just about survived a shipwreck en route 'at Skerries in the late Storm'.

According to George Petrie (of whom more below), Edward was the youngest, though the details on John's gravestone (maybe not always to be trusted) suggest that he was the youngest (1776-1828). Edward was born in February 1773.

It seems most likely that Anthony and Edward (and maybe John if he's older than his gravestone suggests) would have had lessons from Robert Barnes who was Armagh Cathedral organist between 1759 and 1774.

After 1774, Barnes was 'reassigned' to the role of Vicar Choral, due to his 'insufficiencies' as an organist! His successor on the fine c.1765 organ by John Snetzler, Dr Langrish Doyle (organist from 1776 to 1780), may also have given the Bunting boys some tuition.

Tragedy struck with the death of the boys' father around 1782.

Anthony (1765-1851) by then was organist of St Peter's Church in Drogheda. The church organ, installed in 1771, had also been built by John Snetzler in London, and just about survived a shipwreck en route 'at Skerries in the late Storm'.

Above: Armagh Cathedral Choir

And so, at the age of

nine, Edward, if not also John, went to live in Drogheda with his

brother Anthony who gave him music lessons for two years.

Progress was

so good that, in 1784, young Edward was asked by William Ware to deputise for him

at the organ of St. Anne's Parish Church in Belfast while Ware was away on business

in London.

The new St. Anne's Church had been built on the site of the first Brown Linen Hall in the new and developing Donegall Street. The church was paid for (£10,000) by Belfast's landlord, Arthur, fifth Earl of Donegall. The present day St Anne's Cathedral now occupies that same site.

The new St. Anne's Church had been built on the site of the first Brown Linen Hall in the new and developing Donegall Street. The church was paid for (£10,000) by Belfast's landlord, Arthur, fifth Earl of Donegall. The present day St Anne's Cathedral now occupies that same site.

Arthur Young, writing in his Tour in Ireland on 23 July 1776 commented:

'… His Lordship is also building a new church, which is one of the lightest and most pleasing I have any where seen: it is 74 by 54, and 30 feet high to the cornice; the [a]isles separated by a double row of columns; nothing can be lighter or more pleasing.'

Samuel Lewis, in his 1837 Topographical Dictionary mentions the 'lofty Ionic tower surmounted by a Corinthian cupola covered with copper'.

Left: St. Anne's, Belfast's parish church. An engraving by John Thomson from George Benn's 1823 History of Belfast.

The low portico here (and below) was replaced with tall Corinthian columns in 1832.

The low portico here (and below) was replaced with tall Corinthian columns in 1832.

The parish church possessed

the only organ in Belfast, gifted by the Earl and installed in 1781. Like Armagh, Hillsborough and Drogheda, it was another instrument by John Snetzler. For more information on the St Anne's organ see the PDF on the right:

|

St Anne's Parish Church organ and organists.pdf Size : 345.287 Kb Type : pdf |

The engraving of St Anne's on the right is from the 1894 Ulster Journal of Archeology, Vol.1, p.18, and is said to be 'From an unpublished copperplate by J. Thompson [sic]'.

Belfast's Mr. Music at that time, William Ware (1757-1826), was another product of Armagh Cathedral and so he likely knew the Bunting family long before young Edward was asked to cover for Ware while he was away.

Ware's wife ran a girl's boarding school at their home. He gave lessons there in addition to his extensive teaching practice (including guitar) in Belfast and beyond. He tuned, regulated and repaired instruments, promoted concerts and he was also an agent for Broadwood and Southwell pianos and harpsichords.

Ware's wife ran a girl's boarding school at their home. He gave lessons there in addition to his extensive teaching practice (including guitar) in Belfast and beyond. He tuned, regulated and repaired instruments, promoted concerts and he was also an agent for Broadwood and Southwell pianos and harpsichords.

It was most likely a boastful exaggeration of the elderly Bunting to Petrie, perhaps fifty years later, that during the eleven-year-old's first visit to Belfast, he was said to be a

better organist than Ware.

If true, it's hard to explain the fact that, without further ado, Bunting was articled to Ware as his apprentice in 1784.

If true, it's hard to explain the fact that, without further ado, Bunting was articled to Ware as his apprentice in 1784.

LH pic: William Ware c.1790., a miniature by the Irish artist George Place (c.1760-1805).

Pic copyright © National Museums NI.

Pic copyright © National Museums NI.

As Roy Johnston has noted (Bunting's Messiah, Belfast 2003), Ware had already advertised in the Belfast News-Letter three years earlier (28 September 1781, page 3), for an apprentice, aged between nine and twelve. 'A fee is required. None need apply who cannot be well recommended, and who has not a Taste for the Musical Profession'.

Did brother Anthony Bunting pay that 'required fee'?

Did brother Anthony Bunting pay that 'required fee'?

During Bunting's time in Belfast - he stayed for 35

years! - he lodged with the McCracken family in Rosemary Lane, treated very much as a member of the family rather than a lodger and known to them as 'Atty' (perhaps an Ulster-Scots version of 'Eddy'?!).

It was a family at the very centre of the social and political problems of the time, and the young Edward Bunting, while close to them and involved in political debate, seems to have remained outside most of the actual intrigue. Head of the family was Capt. John McCracken (c.1721-1803), ship owner, merchant and entrepreneur. He was married to Ann Joy (1730-1814), sister of Henry and Robert Joy, proprietor/editors of the Belfast News-Letter. The McCracken family were all members of the Third Presbyterian Church, part of that amazing cluster of Presbyterian churches in Rosemary Street.

It was a family at the very centre of the social and political problems of the time, and the young Edward Bunting, while close to them and involved in political debate, seems to have remained outside most of the actual intrigue. Head of the family was Capt. John McCracken (c.1721-1803), ship owner, merchant and entrepreneur. He was married to Ann Joy (1730-1814), sister of Henry and Robert Joy, proprietor/editors of the Belfast News-Letter. The McCracken family were all members of the Third Presbyterian Church, part of that amazing cluster of Presbyterian churches in Rosemary Street.

The family (five sons and two daughters) were reformers, liberal thinkers, strong supporters of the poorhouse, and very much involved with the United Irishmen. Edward Bunting was close to the youngest son, John McCracken (1772-1834), who was interested in music.

Mary Ann McCracken (1770-1866), a tremendous support for 'Atty' (her talent for maths was particularly helpful in keeping his accounts in order) was also interested in music. She was progressive in outlook, a real advocate of women's and children's rights and secretary of the Charitable Society's Ladies' Committee.

Her brother, Henry Joy McCracken (1767-1798), led the United Irishmen to defeat at the Battle of Antrim. He was captured in Carrickfergus and executed outside Belfast's Market House.

Mary Ann McCracken (1770-1866), a tremendous support for 'Atty' (her talent for maths was particularly helpful in keeping his accounts in order) was also interested in music. She was progressive in outlook, a real advocate of women's and children's rights and secretary of the Charitable Society's Ladies' Committee.

Her brother, Henry Joy McCracken (1767-1798), led the United Irishmen to defeat at the Battle of Antrim. He was captured in Carrickfergus and executed outside Belfast's Market House.

The PDF on the right gives a potted history across this period and through to the 1840s. It's from Andrew George Malcolm's The History of the General Hospital Belfast, and the other Medical Institutions of the town, Belfast, 1851.

|

Historical Background by Malcolm 1851.pdf Size : 183.629 Kb Type : pdf |

It seems

that William Ware and his young apprentice got on reasonably well from 1784, for we hear nothing more of Bunting for the next eight years, apart

from Petrie's account, relaying tales told by Bunting in his later years.

The artist, archaeologist and folk song collector George Petrie (1790-1866), a friend of Bunting's old age, describes the attitudes of the young teenager-about-town and gives a most unflattering picture of the adolescent Bunting. (Our Portrait Gallery, No.XLI, simply signed 'P', for the Dublin University Magazine, Vol.29, No.169, January 1847, is given in full in the PDF below).

George Petrie:

In addition to his duties as assistant or sub-organist at

the church, Bunting had also to act as deputy teacher to Mr. Ware's

pupils on the pianoforte throughout the neighbouring country.

The

zeal of the young master to fulfil his duties was often productive of

the most ludicrous results. His young lady pupils, who were often many

years older than himself, were accustomed to take his reproofs with

anything but angelic temper, and I've heard him tell how a Miss Stewart,

of Wilmont [Dunmurry], in the County of Down, was so astonished at his audacity,

that she indignantly turned round upon him and well boxed his ears.

After

a few years spent in this manner, he became a professor on his own

account, and as his abilities as a performer had become developed, his

company was courted by the higher class of the Belfast citizens, as well

as by the gentry of its neighbourhood. In short, the boy prodigy became

an idol amongst them.

Courted and

caressed, flattered and humoured, he should have paid the usual penalty

for such pampering - that his temper should have become pettish, and his

habits wayward and idle - he did everything as he liked, with a

reckless disregard of what might be thought of it.

Wayward and pettish he remained through life, and for a long period - at least occasionally - idle, and, I fear dissipated; for hard drinking was the habit of the Belfastians in those days. But, while still young, not more than 19, an event occurred, which gave his ardent and excitable temperament a worthy object of ambition on which to employ it, and which necessarily required a cultivation of his powers, to enable him to effect it. The event I allude to was the assemblage at Belfast, in 1792, of the harpers from all parts of Ireland.

Right: A PDF with a complete transcript of George Petrie's Portrait of his friend Edward Bunting, published in the Dublin University Magazine, January 1847.

|

Bunting - A Portrait, 1847.pdf Size : 316.479 Kb Type : pdf |

The assembly of harpers in Belfast (only referred to, somewhat incorrectly, as the 'Belfast Harp Festival' since 1903, following that year's Irish Harp Festival promoted by the Linen Hall Library), gave Edward Bunting his sense of direction and purpose in life.

Before that, here's a fascinating glimpse of Bunting debating politics with Wolfe Tone (1763-1798), Thomas Russell (1767-1803) - 'P.P.' in Tone's diary - and friends.

Before that, here's a fascinating glimpse of Bunting debating politics with Wolfe Tone (1763-1798), Thomas Russell (1767-1803) - 'P.P.' in Tone's diary - and friends.

Russell was

one of the founders and a leading member of the United Irishmen. He

became librarian for the Belfast Society for Promoting Knowledge (now

Linen Hall Library) in 1794.

Much admired by Mary Ann McCracken ('a model of manly beauty'), Russell was held without trial in 1796, released in 1802, and a year later he was executed for his part in Robert Emmet's 1803 rebellion.

Much admired by Mary Ann McCracken ('a model of manly beauty'), Russell was held without trial in 1796, released in 1802, and a year later he was executed for his part in Robert Emmet's 1803 rebellion.

Read more about Russell here.

LH pic: Thomas Russell from Ireland in '98 ... based upon the published volumes and some unpublished MSS. of the late Dr. R. R. Madden ... Edited by J. Bowles Daly., London 1888, p.370

In his diary for Sunday, 23 October 1791, Tone writes:

'Went at 9 to the Washington club. Argument between Bunting and Boyd of Ballycastle [Hugh Boyd, soon to be high sheriff and and M.P. for Co.Antrim]. Boyd pleasant*; persuaded myself and P.P. that we were hungry. Went to the Donegall Arms and supped on lobsters, &c. Drunk. Very ill-natured to P.P. ...'

*Charlotte Milligan Fox (Annals of the Irish Harpers, London 1911) suggests that this implies Bunting was the opposite, i.e. unpleasant. Fox and Petrie remain the two major sources for information about Bunting.

On Tuesday, 25 October 1791, Tone records a dinner at [Samuel] McTier's [a founder member, both of the Charitable Society and of the United Irishmen]:

'W[addell] Cunningham, [John] Holmes, Dr [William] Bruce, &c.

A furious battle which lasted two hours on the Catholic [emancipation] question. As usual neither party convinced. ... Bruce an intolerant high priest. ... Almost all the company of his opinion, excepting P.P. [Russell] who made desperate battle, McTier and me. Against us, Bruce, W. Cunningham, [Cunningham] Greg, Holmes, Bunting, H. Joy, Ferguson dubitante et cetera all protesting their liberality and good wishes to the R[oman] C[atholics]. ... Broke up rather ill disposed to each other. More and more convinced of the absurdity of arguing over wine. ...'

'Went at 9 to the Washington club. Argument between Bunting and Boyd of Ballycastle [Hugh Boyd, soon to be high sheriff and and M.P. for Co.Antrim]. Boyd pleasant*; persuaded myself and P.P. that we were hungry. Went to the Donegall Arms and supped on lobsters, &c. Drunk. Very ill-natured to P.P. ...'

*Charlotte Milligan Fox (Annals of the Irish Harpers, London 1911) suggests that this implies Bunting was the opposite, i.e. unpleasant. Fox and Petrie remain the two major sources for information about Bunting.

On Tuesday, 25 October 1791, Tone records a dinner at [Samuel] McTier's [a founder member, both of the Charitable Society and of the United Irishmen]:

'W[addell] Cunningham, [John] Holmes, Dr [William] Bruce, &c.

A furious battle which lasted two hours on the Catholic [emancipation] question. As usual neither party convinced. ... Bruce an intolerant high priest. ... Almost all the company of his opinion, excepting P.P. [Russell] who made desperate battle, McTier and me. Against us, Bruce, W. Cunningham, [Cunningham] Greg, Holmes, Bunting, H. Joy, Ferguson dubitante et cetera all protesting their liberality and good wishes to the R[oman] C[atholics]. ... Broke up rather ill disposed to each other. More and more convinced of the absurdity of arguing over wine. ...'

Above: Theobald Wolfe Tone

In 1791, an initial steering committee of Henry Joy, Dr. James McDonnell, Robert Simms, John Scott and Robert Bradshaw (the Secretary and Treasurer) set about organising the assembly of harpers. They were members of the Belfast Reading Society (shortly to change its name to the Belfast Society for Promoting Knowledge), founded to set up a town library, which would become the Linen Hall Library. Planning progressed quickly, not least because time was short.

The PDF on the right

details the increased committee - note its gender balance! - and

thoughts on premiums (prizes) and other proposals. It's an undated

document, held by the Linen Hall Library (Beath MSS), much of it being a

draft for the Belfast News-Letter article, 27 April 1792. See the third thumbnail/pic below.

|

Harpers' Assembly Committee membership and proposals.pdf Size : 130.479 Kb Type : pdf |

Note the genuine interest in finding 'obsolete airs'. Of particular interest is the wish that 'the Reverend Mr. Andrew Bryson of Dundalk be requested to assist, as a person vers’d in the [Irish] language and antiquities of the Nation; And that Mr. W Weare [Ware], Mr. Edward Bunting and Mr. John Sharpe [organist to John O'Neill of Shane's Castle] be requested to attend as practical musicians'. None were named in the published press article.

In the event, it seems that Bryson, Ware and Sharpe were 'no shows' for the assembly.

It was left to Edward Bunting to transcribe the music played by the harpers.

In the event, it seems that Bryson, Ware and Sharpe were 'no shows' for the assembly.

It was left to Edward Bunting to transcribe the music played by the harpers.

Clicking on the thumbnails below reveals some of the contemporary newspaper / print material for the harpers' assembly.

Interestingly, with just a few days' notice, both the harpers' assembly and the 'classical' concert had to be moved forward by a day because of a date clash with the Tuesday evening Coterie (unusually of both ladies and gentlemen) which met in the Assembly Rooms each month, following a 'Promenade'.

No.1

No.2

No.3

No.4

No.5

A handbill calling for subscribers, Dec. 1791. Source: Beath MSS., Linen Hall Library (also quoted by Bunting in his 1840 Collection). Most also in BNL (Belfast News-Letter), 23-27 December 1791, page 3. Note: 'a skilful Musician to transcribe and arrange the

most beautiful and interesting parts of their Knowledge'.

An advertisement for a subscribers' meeting, BNL, 17-20 April 1792, page 3.

A supportive article which follows directly after Robert Bradshaw's notice to harpers (shown in full below). BNL 24-27 April 1792, page 3.

It helps to have a newspaper proprietor and editor on your committee!

It helps to have a newspaper proprietor and editor on your committee!

A call for subscription payments and ticketing details, BNL 3-6 July 1792, page 3.

A 'classical' concert on the harp assembly's first evening, BNL 3-6 July 1792, page 3.

Belfast News-Letter 27 April 1792:

National Music of Ireland

A Respectable Body of the Inhabitants of Belfast

having published a plan for reviving the ancient

Music of this country, and the project having met with

such support and approbation as must insure success to

the undertaking, PERFORMERS ON THE IRISH HARP are

requested to assemble in this town on the tenth day of

July next, when a considerable sum will be distributed in

Premiums, in proportion to their respective merits.

It being the intention of the Committee that every

Performer shall receive some Premium, it is hoped that

no Harper will decline attending on account of his hav-

ing been unsuccessful on any former occasion.

The last paragraph in the advertisement above refers to problems encountered at

the competitive harp 'balls' held at Granard, Co. Longford, in the 1780s. These had been financed by a successful local businessman, John Dungan, then working out of Copenhagen. Inspired by Highland piping competitions, he financed three harpers' competitions in Granard, 1784, 1785 and 1786. He then gave up, disillusioned by the bickering amongst the harpers about the premiums or prizes - especially when the same three harpers always won: First, Charles Fanning, Second, Arthur O'Neill and Third, Rose Mooney.

Some writers have questioned the motives of the Belfast harp assembly organisers, who were closely connected to the United Irishmen, speculating about the coincidence of the assembly with the third anniversary celebration of the storming of the Bastille, and the series of political meetings with Wolfe Tone and the United Irishmen.

Some writers have questioned the motives of the Belfast harp assembly organisers, who were closely connected to the United Irishmen, speculating about the coincidence of the assembly with the third anniversary celebration of the storming of the Bastille, and the series of political meetings with Wolfe Tone and the United Irishmen.

The PDF on the right is an account of the 1792 assembly of harpers published in the Ulster Journal of Archeology,

Vol.1, No.2, in January 1895, pp.120-127. It was written by Robert

Young, JP, CE., and lists the repertoire along with some biographical

notes.

|

Irish Harpers Belfast 1792.pdf Size : 486.854 Kb Type : pdf |

Eleven harpers (including a Welshman), aged from 15 to 97, six of them blind, competed for a first prize of ten guineas in the elegant first floor Assembly Rooms of the Belfast Exchange. Bunting, then aged 19, would have been kept busy!

Harper

Denis Hempson

Charles Byrne

Daniel Black

Arthur O'Neill

Charles Fanning

Hugh Higgins

Rose Mooney

Patrick Quin

James Duncan

William Carr

?? Williams

Denis Hempson

Charles Byrne

Daniel Black

Arthur O'Neill

Charles Fanning

Hugh Higgins

Rose Mooney

Patrick Quin

James Duncan

William Carr

?? Williams

Age

97

80

75

58

56

55

52

47

45

15

??

97

80

75

58

56

55

52

47

45

15

??

Where from

Co. Derry

Co. Leitrim

Co. Derry

Co. Tyrone

Co. Cavan

Co. Mayo

Co. Meath

Co. Armagh

Co. Down

Co. Armagh

Wales

Co. Derry

Co. Leitrim

Co. Derry

Co. Tyrone

Co. Cavan

Co. Mayo

Co. Meath

Co. Armagh

Co. Down

Co. Armagh

Wales

Comment

Blind

-

Blind

Blind

-

Blind

Blind

Blind

-

-

Died going home

-

Blind

Blind

-

Blind

Blind

Blind

-

-

Died going home

Assembly Rooms, Belfast Exchange, engraved by J. Thomson

The first prize (Ten Guineas) was awarded to Charles Fanning, second prize (Eight Guineas) to Arthur O'Neill. Yet again, Rose Mooney came third. Bunting later recalled (1840 Collection) that everyone else (presumably including Rose Mooney?) was awarded Six Guineas and that Fanning was not the best performer, but won first prize because of the popularity of The Coolin 'with modern variations'.

Bunting also noted that 'When the proceedings were terminated, all the harpers were invited to dinner by Dr McDonnell; "and if we had been Peers of the Realm," says O'Neill, "we could not have been better treated; the assiduity of the Doctor and his family, to make us happy, was more than I can describe".'

Bunting also noted that 'When the proceedings were terminated, all the harpers were invited to dinner by Dr McDonnell; "and if we had been Peers of the Realm," says O'Neill, "we could not have been better treated; the assiduity of the Doctor and his family, to make us happy, was more than I can describe".'

The thumbnails pics below are of four of those harpers:

No.1 - Denis Hempson, engraving 'from an original drawing by E. Scriven', from Bunting's 1809 Collection.

No.2 - Charles Byrne, 'sketched by Miss O'Reilly of Scarva, 16th August 1810', from Fox, Annals, 1911.

No.3 - Arthur O'Neill, 'from an old engraving by T. Smith, Belfast', from Fox, Annals, 1911.

No.4 - Patrick Quin, engraving by Henry Brocas, Monthly Pantheon, No.17, October 1809,

after a portrait by Eliza H. Trotter.

No.1 - Denis Hempson, engraving 'from an original drawing by E. Scriven', from Bunting's 1809 Collection.

No.2 - Charles Byrne, 'sketched by Miss O'Reilly of Scarva, 16th August 1810', from Fox, Annals, 1911.

No.3 - Arthur O'Neill, 'from an old engraving by T. Smith, Belfast', from Fox, Annals, 1911.

No.4 - Patrick Quin, engraving by Henry Brocas, Monthly Pantheon, No.17, October 1809,

after a portrait by Eliza H. Trotter.

Left: This 1790 aquatint of the Assembly Rooms in the Exchange is by Thomas Malton "the Younger" (1748-1804).

Originally an arcaded market-house, the Exchange was built in 1769. Lord Donegall then invited the London architect Sir Robert Taylor to add this elegant first floor Assembly Rooms in 1776.

Originally an arcaded market-house, the Exchange was built in 1769. Lord Donegall then invited the London architect Sir Robert Taylor to add this elegant first floor Assembly Rooms in 1776.

Edward Bunting:

I was appointed to attend the Festival and to take down the various airs played by the different harpers. I was particularly cautioned against adding a single note to the old melodies which would seem to have been preserved pure and handed down unalloyed through a long succession of ages.

Wolfe Tone's diary entries, coloured by his hangovers, record the event in less than enthusiastic terms!

July 11th:

July 12th:

July 13th:

Rise with a great headache; stupid as a mill horse … All go to Harpers at one; poor enough; ten performers; seven execrable, three good, one of them, Fanning far the best. No new musical discovery; believe all the good Irish tunes are already written …

July 12th:

Rise again with a headache resulting from late hours … lounge to harpers …

July 13th:

Rise again with headache … Belfast not half so pleasant this time as last; politics just as good or better; everything else worse … generally in low spirits … the Harpers again, strum, strum, and be hanged …

The PDF on the right has a transcript of the Belfast News-Letter's report on the first day. Its tone, as to be expected, is positive. The write-up includes details of what each harper played.

Belfast News-Letter, 10-13 July 1792, page 3.

Belfast News-Letter, 10-13 July 1792, page 3.

|

Harpers' Assembly First Day listing i.pdf Size : 194.665 Kb Type : pdf |

This PDF has the Northern Star's

view of the assembly after all four days. For a newspaper which was the

mouthpiece of the United Irishmen, there's a surprisingly disparaging

(perhaps honest?) view taken of the old harpers: 'The Bard of former

times ... is but very faintly represented by a modern Irish Harper'. Northern Star, 18 July 1792, page 3.

|

Northern Star Summary of the 1792 Harpers.pdf Size : 171.816 Kb Type : pdf |

Unlike Wolfe Tone, Bunting was fired with enthusiasm for the music he had heard. Later in 1792, along with Richard Kirwan (1733-1812), geologist, chemist, enthusiast for Irish music and eventually President of the Royal Irish Academy, the pair travelled to Mayo and probably Galway, collecting more airs. Some time later, Bunting also collected in Co. Tyrone and in Co. Derry, spending time with Denis Hempson in Magilligan.

Advance notice for the harpers' assembly had been surprisingly short. The same has to be said for Bunting's first publication. It has usually been dated as 1796 (including by Bunting himself in the Preface to his 1840 Collection: 'the first and only collection of genuine Irish harp music given to the world up to the year 1796'), though the first edition, from Preston & Co in London, bears no date at all. Reinforcing a revised date of 1797, Bunting was only advertising for subscribers as late as September / early October 1796.

This PDF is from the Dublin Evening Post,

Saturday 8 October 1796, page 1. It seeks 'Half-a-Guinea' subscriptions

for 'The First Volume of Mr. Bunting's Collection of the National Music of Ireland'.

He mentions that the publication is under the patronage of the Belfast

Society for Promoting Knowledge. Note that those listed to receive

subscriptions include his brothers: Anthony Bunting in Drogheda and John

Bunting in Newry.

|

Bunting Subscriber search 1796.pdf Size : 679.118 Kb Type : pdf |

So, most likely, Bunting's first book A General Collection of the Ancient Irish Music appeared in 1797: sixty-six native Irish Airs 'never before published'. See it here, courtesy of the Irish Traditional Music Archive. The first edition was "Printed & sold by Preston & Son, at their Wholesale Warehouses, 97 Strand [London]", and pirated editions soon followed, including those in Dublin by Hime, 24 College Green, and Power, 4 Westmoreland Street.

The full title is A General Collection of the Ancient Irish Music, containing a variety of Admired Airs, never before published, and also the Compositions of Conolan & Carolan / collected from the Harpers &c. in the different Provinces of Ireland, and adapted for the Piano-Forte, with a Prefatory Introduction by Edward Bunting. Vol. 1.

Martha McTier (letter to Dr. Drennan, December 1797):

Have you heard Bunting's Irish music? …To me they are sounds might make Pitt melt for the poor Irish - not a copy is now to be got - but I hear they are very unjustly going to reprint them in Dublin [a reference to pirated editions].

Martha McTier (letter to Dr. Drennan, February 1798):

Have you got the Irish music - it is the rage here - it would be worth your while to try if you could hear him [Bunting] play his Irish music - sugar plumbs or sweetys is his greatest temptation, for he despises both money and praise and is thought a good-hearted original.

Charlotte Milligan Fox (1911):

The book stands as the earliest standard authority. View it with regard to its after-effect in popularising and saving Irish music, it must be classed as an epoch-making book. Not that its circulation was very extensive, for indeed it brought little profit to the young man who gave it to the world.

The subject of the compiler and of his enthusiastic

supporters in Belfast was accomplished indirectly through the medium of

others who followed in Bunting's track and gleaned the reward of his

labours. In short, he gave the material and inspiration to Moore

for his Irish melodies which are known and sung in every country of the

civilised world.

'Gave the material' is not quite the right way to express it! When Moore's first volume appeared, eleven of its sixteen melodies were derived from Bunting's collection and Moore continued to draw extensively upon the collection in subsequent volumes - much to Bunting's extreme disapproval!

Thomas Moore:

Thomas Moore:

Considering the thorn I have been in poor Bunting's side

by supplanting him in the one great object of his life (the connection

of his name with the fame of Irish Music) the temper in which he now

speaks of my success (for some years since he was rather termagant on

the subject) is not a little creditable to his good nature and good

sense.

Speaking of the use I made of the first volume of airs published by him he says: "They were soon adapted as vehicles for the most beautiful popular songs that perhaps have ever been composed by any lyric poet."

Speaking of the use I made of the first volume of airs published by him he says: "They were soon adapted as vehicles for the most beautiful popular songs that perhaps have ever been composed by any lyric poet."

He complains strongly, however, of the alterations made

in the original airs, and laments that "the work of the Poet was

accounted of so paramount an interest that the proper order of song

writing was in many instances inverted, and instead of the words being

adapted to the tunes, the tune was too often adapted to the words: a solecism which could never have happened had the reputation of the

writer not been so great as at once to carry the tunes he designed to

make use of, altogether out of their old sphere among the simple

tradition-loving people of the Country with whom in truth many of the

new melodies to this day are hardly suspected to be themselves."

He lays the blame of all these alterations upon Stevenson, but poor Sir

John was entirely innocent of them; as the whole task of selecting the

airs and in some instances shaping them thus, in particular passages, to

the general sentiment, which the melody appeared to me to express was

undertaken solely by myself.

Had I not ventured on these very admissible liberties many of the songs now most known and popular would have been still sleeping with all their authentic dross about them in Mr Bunting's first Volume.

Had I not ventured on these very admissible liberties many of the songs now most known and popular would have been still sleeping with all their authentic dross about them in Mr Bunting's first Volume.

The same charge is brought by him respecting those airs, which I took

from the Second Volume of his collection. "The beauty of Mr Moore's

words," he says, "in a great degree atones for the violence done by the

musical arranger to many of the airs, which he has adopted."

Above: Thomas Moore (1779-1852), from a portrait by Sir Thomas Lawrence.

Right: Sir John Stevenson (1761-1833) from an 1825 engraving. He arranged many of Moore's Irish Melodies.

Right: Sir John Stevenson (1761-1833) from an 1825 engraving. He arranged many of Moore's Irish Melodies.

Bunting only came round to a more generous attitude to

Moore at the end of his life - after many years of feeling cheated

by both Moore and Stevenson.

If Bunting's book wasn't exactly a best-seller, then life in his adopted household would certainly have provided a suitable plot for one!

Henry Joy McCracken (named after his maternal uncle) was

executed after the abortive 1798 rebellion but Bunting continued to

reside with the McCracken family in Rosemary Lane (now Rosemary Street), apparently taking

little or no active part in the hot and heavy politics.

Henry's sister, Mary Ann, remained one of Bunting's closest friends and advisers till the end of his life. She was two years older than Bunting.

Henry's sister, Mary Ann, remained one of Bunting's closest friends and advisers till the end of his life. She was two years older than Bunting.

Left: Mary Ann McCracken (1770-1866), from a miniature painted around 1801.

By the turn of the century, despite martial law and curfews following the abortive 1798 rebellion, normal life gradually resumed. Bunting had now succeeded William Ware as the Belfast musician. In 1801 he promoted eight weekly summer subscription concerts in the Donegall Arms in Donegall Place along with a concert of excerpts from Handel's oratorios in St. Anne's Church. There were more concerts the following year and later - and probably others which were not advertised in the newspapers.

RH thumbnail pics (L to R) - click as required:

No.1 - an advertisement for a concert which included a Piano Concerto played by Mr. Bunting (Belfast News-Letter (BNL), 16 August 1799.

No.2 - an advertisement for Bunting's Eight Subscription Concerts, BNL 21 July 1801 (mistakenly printed as 1081!).

No.3 - Details of the Handel concert in St Anne's with Charles Incledon, tenor, and Mrs Elizabeth Addison, soprano, BNL 31 July 1801.

No.1 - an advertisement for a concert which included a Piano Concerto played by Mr. Bunting (Belfast News-Letter (BNL), 16 August 1799.

No.2 - an advertisement for Bunting's Eight Subscription Concerts, BNL 21 July 1801 (mistakenly printed as 1081!).

No.3 - Details of the Handel concert in St Anne's with Charles Incledon, tenor, and Mrs Elizabeth Addison, soprano, BNL 31 July 1801.

In addition to teaching, performing and promoting

concerts, Bunting was also working towards his next collection of

'Ancient Irish Music'. Not without controversy.

His travels took him to Connacht again in 1802, this time with an Irish scholar, Patrick Lynch, to write down the Irish words to the songs. The manuscripts, held at Queen's University in Belfast (QUB), show an extensive collection of Irish texts. Lynch also travelled on his own to collect airs at Bunting's behest. One of the manuscripts at QUB is catalogued thus:

His travels took him to Connacht again in 1802, this time with an Irish scholar, Patrick Lynch, to write down the Irish words to the songs. The manuscripts, held at Queen's University in Belfast (QUB), show an extensive collection of Irish texts. Lynch also travelled on his own to collect airs at Bunting's behest. One of the manuscripts at QUB is catalogued thus:

MS4/24 Patrick Lynch’s Manuscript Journal, 1802, 17 pp. including titles of 193 Songs in Irish. 9 pp.; words of Songs in Irish. 7 pp., (with blank pages). Note on blank page at beginning of journal, ‘This tour was undertaken by order of Mr. E. Bunting about the 1st of May – by Patrick Lynch, in the year 1802’. Limp cover.

Alas, the Irish texts never made it into Bunting's second collection of 1809. Politics and divided loyalties again!

Bunting and the McCrackens were very close to Thomas Russell, the first librarian to the Belfast Society for Promoting Knowledge, fore-runner of the Linen Hall Library. Russell, as already mentioned above, was put on trial in Downpatrick in 1803 for his part in the failed Robert Emmet Rising.

Dr McDonnell, much to his later regret, put up some money towards the reward for Russell. Patrick Lynch, by all accounts, found himself in that impossible position between a rock and a hard place. He had to turn King’s Evidence against Russell. Former friends parted company.

For some years McDonnell was definitely outside the circle of Bunting/McCracken friends, though fences seemed to be mended within a few years. Patrick Lynch, however, went to ground and disappeared.

Bunting and the McCrackens were very close to Thomas Russell, the first librarian to the Belfast Society for Promoting Knowledge, fore-runner of the Linen Hall Library. Russell, as already mentioned above, was put on trial in Downpatrick in 1803 for his part in the failed Robert Emmet Rising.

Dr McDonnell, much to his later regret, put up some money towards the reward for Russell. Patrick Lynch, by all accounts, found himself in that impossible position between a rock and a hard place. He had to turn King’s Evidence against Russell. Former friends parted company.

For some years McDonnell was definitely outside the circle of Bunting/McCracken friends, though fences seemed to be mended within a few years. Patrick Lynch, however, went to ground and disappeared.

Before all that, in 1801, the records of the First Presbyterian Church, Rosemary Street, reveal Bunting as entrepreneur. The church received 'a very liberal proposal from Mr. Edward Bunting respecting the purchase of an organ'.

Sadly the offer was turned down, but 'with thanks to Mr. Bunting in the warmest terms of gratitude'.

Did he already know the organ builder Stephen White at this time? Was this a fledgling business partnership?

Sadly the offer was turned down, but 'with thanks to Mr. Bunting in the warmest terms of gratitude'.

Did he already know the organ builder Stephen White at this time? Was this a fledgling business partnership?

Five years later Bunting was advising the Second Presbyterian Church next door in Rosemary Street on a new organ to be built by a certain Stephen White from London. No surprise then that in 1806 Bunting became the organist for the Second Congregation.

This was only the second organ in Belfast (the first having been that of St Anne's Parish Church). White's casework for Rosemary Street, with its three towers, is 'English Classical' in style and clearly follows in the style of Snetzler.

This was only the second organ in Belfast (the first having been that of St Anne's Parish Church). White's casework for Rosemary Street, with its three towers, is 'English Classical' in style and clearly follows in the style of Snetzler.

RH pic: Organ and Choir Loft, Rosemary Street, from S. Shannon Millin's History of the Second Congregation of Protestant Dissenters in Belfast, Belfast 1900. Illustration by J. Vinycomb.

Tradition, long since disproved, had it that the organ

was formerly erected in St George's Chapel, Windsor, and had been played

by Handel. In 1796, when St George's Chapel installed a fine new organ by Samuel Green, its old organ found a new home rather closer to Windsor than Belfast!

Over the years there were various repairs to Stephen White's 1806 Belfast instrument.

Over the years there were various repairs to Stephen White's 1806 Belfast instrument.

In 1857 it was shipped to Thomas J Robson, 'Organbuilder to Her

Majesty', in London for a major rebuild. When the congregation moved

from Rosemary Street to All Souls' Church, Elmwood Avenue, in 1896, the

organ followed a couple of years later. Since 1928, that historic Stephen White organ has found a further lease of life in the First Presbyterian Church (Non-Subscribing), Newry.

The PDF on the right gives a more detailed account of the instrument, including specifications, complete newspaper articles and more illustrations.

|

Second Presbyterian Church organ 1806.pdf Size : 890.849 Kb Type : pdf |

This next PDF details the known instruments built by Stephen White, including the organs and Irish harps likely made in his Belfast workshop in Orr's-entry, High-street.

|

Stephen White organ-builder.pdf Size : 1438.345 Kb Type : pdf |

Belfast News-Letter (Friday, 5 September 1806, page 2):

We are happy to inform the public, that the first organ which has been introduced into a Protestant Dissenting Meeting House, in Ulster, will be touched by the masterly hand of Mr. Bunting on Sunday next [7 September 1806].

(Some days later, Tuesday, 9 September 1806, page 2):

On Sunday last, the new Organ in the Second Congregation of Protestant Dissenters of Belfast, was opened by Mr. Bunting, with the music of the old 100th psalm, the composition, as Handel said, of Martin Luther, the Reformer. The instrument was conducted with chaste gravity, suited to the simplicity of Presbyterian worship; and the finest effect produced by an admirable finger directed by pure taste.

That "admirable finger" seemed to have had a little more

business sense when organising concerts than when publishing music.

He was still working towards his second Collection of 'Ancient Irish Music' and he was now organist for the Second Congregation, but his concert promotions at this time included the two visits to Belfast in 1807 (two concerts in the Theatre) and 1808 (one concert in the Exchange Assembly Room) by the great Italian soprano Angelica Catalani (1780-1849), only 26 years old on her first visit.

The concerts were given 'under the direction of Mr. Bunting, who will preside at the Piano-Forte'.

He was still working towards his second Collection of 'Ancient Irish Music' and he was now organist for the Second Congregation, but his concert promotions at this time included the two visits to Belfast in 1807 (two concerts in the Theatre) and 1808 (one concert in the Exchange Assembly Room) by the great Italian soprano Angelica Catalani (1780-1849), only 26 years old on her first visit.

The concerts were given 'under the direction of Mr. Bunting, who will preside at the Piano-Forte'.

LH pic: Advertisement from the Belfast News-Letter, 15 September 1807, page 3.

Pic below, right: Angelica Catalani, painted by Elisabeth Louise Vigée-LeBrun in 1806.

At that time, Catalani must have been at, or nearly at, the peak of her ability as 'the great Italian soprano'. Fifteen years later, it appeared she was past her best!

This critical review is from page 3 of the Durham County Advertiser for Saturday 27 September 1823:

'Overwhelming as the powers of Catalani are, or rather were, the virtue of singing in tune, in which she never abounded, is less than ever, and the stringed instruments exhibited an extraordinary forbearance in at all qualifying the alacrity at singing, which was exhibited in “Holy, Holy.”'

Over the years, Bunting and Catalani met on a number of occasions. Once, she was so

delighted with Bunting's performance of some of the Irish airs that she took a

diamond ring off her finger and presented the ring to Bunting.

Another anecdote from many years later was recalled by George Petrie:

Another anecdote from many years later was recalled by George Petrie:

Catalani - "Well, my dear Mr. Bunting, how glad I am to see you looking so strong and well".

Bunting, with a shrug - "Ugh, ugh, no madam, I'm growing fat and lazy like an old dog as I am".

Catalani, looking alarmed and thoughtful - "Ah, indeed, Mr. Bunting - and I too am growing fat and lazy, like an old dog as I am - no, that's not the word - like an old bitch, Mr. Bunting, like an old bitch!"

Bunting, with a shrug - "Ugh, ugh, no madam, I'm growing fat and lazy like an old dog as I am".

Catalani, looking alarmed and thoughtful - "Ah, indeed, Mr. Bunting - and I too am growing fat and lazy, like an old dog as I am - no, that's not the word - like an old bitch, Mr. Bunting, like an old bitch!"

RH pic: Angelica Catalani, painted by Elisabeth Louise Vigée-LeBrun in 1806.

1808 was the

year when Belfast's first Irish Harp Society was formed - very much a

product of the 1792 Harpers' Assembly. Relationships apparently now

restored, it was Dr James McDonnell, as he had been in 1792, who was

the major driving force behind the initiative. Arthur O'Neill was the

Society's harp tutor.

Bunting was

one of the founding subscribers and a member of the Society's music

sub-committee. His friend, the organ builder Stephen White, was still in

Belfast and made at least three harps for the Society at £10 each.

LH pic: Seal of the Belfast Harp Society as drawn by Thomas Smyth of J&T Smyth, engravers, Belfast.

It is reprinted here from Volume 7 of the Ulster Journal of Archeology, 1901, page 5.

The November 1808 Harp Society meeting reported that 'Two harps, the workmanship of an ingenious mechanic in this town [Stephen White], were exhibited at the meeting; and we are informed that several more are now making by the artist who has built two organs in this town [for the Second Congregation and for Thomas Hull, the dancing-master], and will be ready for exhibition at the next meeting'.

Read more about that on pages 13 and 14 in the PDF above about Stephen White, organ-builder.

Below are three PDFs with more detailed information about the Society.

Read more about that on pages 13 and 14 in the PDF above about Stephen White, organ-builder.

Below are three PDFs with more detailed information about the Society.

No.1

No.2

No.3

No.2

No.3

is a transcription of a fine article in the 1895 Ulster Journal of Archeology by John Salmon.

is the report of the November 1808 meeting referred to above.

is a newspaper report of the Society's 1809 dinner in honour of Edward Bunting and his work: many toasts were drunk, as presumably were the attendees by the end of the long evening!

is the report of the November 1808 meeting referred to above.

is a newspaper report of the Society's 1809 dinner in honour of Edward Bunting and his work: many toasts were drunk, as presumably were the attendees by the end of the long evening!

|

Belfast's first Irish Harp Society 1808.pdf Size : 180.014 Kb Type : pdf |

|

Harp Society report, Nov 1808.pdf Size : 240.611 Kb Type : pdf |

|

Bunting and the Belfast Harp Society 1809.pdf Size : 350.895 Kb Type : pdf |

The aims of the Society were admirable and in 1809 Irish classes were added for the students. The tutor, using the Rev. William Neilson's An Introduction to the Irish Language (1808), was none other than the piper James Cody who had been collecting airs for Bunting around the North from about 1805.

RH thumbnail pics: No.1 - announcement of meeting to appoint a committee for the Society, May 1808.

No.2 - advertisement for one of the fund-raising balls for the Society, 1811. Note Thomas Hull as Master of Ceremonies.

No.3 - A letter from 1894 recalling the dress code ('Irish manufacture') for the fund-raising balls.

No.2 - advertisement for one of the fund-raising balls for the Society, 1811. Note Thomas Hull as Master of Ceremonies.

No.3 - A letter from 1894 recalling the dress code ('Irish manufacture') for the fund-raising balls.

Alas, the Harp Society gradually ran out of funds and it folded in 1813.

Arthur O'Neill received an annuity of £30 per annum arranged by his one-time pupil, Dr James McDonnell, who described O'Neill in a letter to Bunting, dated 8 November 1838, as 'a man of veracity and integrity, not at all addicted to boasting, or pretending to anything extraordinary, he never affected to compose or alter any tune, but played it exactly as he had been taught by his Master, Hugh O’Neill, for whom he expressed always great veneration'.

Arthur O'Neill received an annuity of £30 per annum arranged by his one-time pupil, Dr James McDonnell, who described O'Neill in a letter to Bunting, dated 8 November 1838, as 'a man of veracity and integrity, not at all addicted to boasting, or pretending to anything extraordinary, he never affected to compose or alter any tune, but played it exactly as he had been taught by his Master, Hugh O’Neill, for whom he expressed always great veneration'.

Arthur O'Neill died in 1816 aged 88.

The Belfast

Irish Harp Society was re-established in 1819, thanks to major funding

from some 300 army officers and personnel from the north of Ireland

stationed in India (mainly in Bengal, presumably working for the East

India Company).

Valentine Rainey [sometimes Rennie], one of Arthur

O'Neill's pupils from the earlier Society (and a nephew of Robert

'Rabie' Burns no less) was the Society's longest-serving harp tutor.

LH pic: Valentine Rainey; RH pic: the Harp Society's premises in Cromac Street, Belfast. Both "old engravings" from the Ulster Journal of Archeology, Vol.7, 1901, were drawn by Thomas Smyth of J&T Smyth, engravers, Belfast.

Once again funds eventually ran out and the Society closed in 1839.

Meanwhile, somehow fitting around his commitments as organist, sometime organ consultant, concert impresario and teacher, Edward Bunting continued to travel in pursuit of more Irish airs.

In September 1808 he was in Sligo, Limerick, Dublin and Drogheda. In 1809, leading up to his new publication he was often in London. By October he was feeling unwell, "perhaps from my great anxiety about this work [the second Collection]. For, as I must have during my long absence lost my business in Belfast, I have nothing to depend on but the sale of this work, for some time at least." (Letter to Mary Ann McCracken, London, 2 October 1809.)

Like his teacher William Ware, and indeed like his brother Anthony, Bunting also earned some money as an agent for the sale of pianos - mainly for the firm of Broadwood.

But sadly, there was no money to be earned from this second collection of Irish Airs published in 1809 as A General Collection of The Ancient Irish Music,

despite an unattributed "original poem", surely by one of his "eminent poets" (see below!), lauding his work in the Belfast

Commercial Chronicle, February 1807. See the PDF on the right.

|

Original Poem re Bunting 1807.pdf Size : 305.278 Kb Type : pdf |

The first

collection had been of harp melodies; this new one (see its Prospectus on the right) was to include songs

with English verse by "eminent poets" and "A Historical and Critical

Dissertation on the Egyptian, British and Irish Harp".

|

Prospectus Bunting 1808.pdf Size : 399.71 Kb Type : pdf |

Moore's first volume of Irish Melodies had been published in 1807 and Bunting's second collection was rushed out to rival Moore's ready success.

But what chance did "eminent poets" like Miss Mary Balfour, who ran a school for young ladies, or Mr. Boyd "the celebrated translator of Dante" or Stott, a Co. Down bard labelled by Lord Byron as "grovelling Stott", have against Thomas Moore?

Nevertheless, it was a beautifully produced volume. Before George Petrie passed judgement he pointed out that the 1809 publication, in the opinion of the musical world, placed Edward Bunting "in the foremost rank of British Musicians", and as the "most accomplished of those of his own country".

But what chance did "eminent poets" like Miss Mary Balfour, who ran a school for young ladies, or Mr. Boyd "the celebrated translator of Dante" or Stott, a Co. Down bard labelled by Lord Byron as "grovelling Stott", have against Thomas Moore?

Nevertheless, it was a beautifully produced volume. Before George Petrie passed judgement he pointed out that the 1809 publication, in the opinion of the musical world, placed Edward Bunting "in the foremost rank of British Musicians", and as the "most accomplished of those of his own country".

See it here, courtesy of the Irish Traditional Music Archive.

Left: Title page of Bunting's second volume, 1809.

George Petrie:

This alas! was the only

reward it procured him. Like his former collection, its sale barely paid

the expenses of its publication. It was too costly, too repulsively

learned with a long historical dissertation on the antiquity of the harp

and bagpipes prefixed, to give it a chance of suiting the tastes or

purses of the class of society which had bought the earlier work.

Bunting was at length glad, for a trifling sum, to transfer it altogether into the hands of Messrs. Clementi; and like its predecessor the work is now rarely to be seen in Ireland.

Bunting was at length glad, for a trifling sum, to transfer it altogether into the hands of Messrs. Clementi; and like its predecessor the work is now rarely to be seen in Ireland.

As the PDF on the right shows, Bunting was well able to defend himself.

|

Bunting defends his 1809 Collection.pdf Size : 165.086 Kb Type : pdf |

During this time, and throughout the rest of his life, Bunting paid frequent visits to London where he met writers and musicians and where he gave performances of Irish music on the piano. Just as John Field had done in earlier years, Bunting was probably demonstrating pianos - Petrie states that he was an especial favourite at Broadwood's and on his last visit to London in 1839, the firm presented him with a grand piano from its factory.

Bunting's stature both in appearance and in Belfast society was such that a visitor to Belfast in 1812 could not fail to notice him.

J. Gamble, Esq.:

J. Gamble, Esq.:

Music was the favourite recreation in Belfast and many were no mean proficients in it. They are probably indebted for this to Mr. Bunting, a man well known in the musical world.

He has an extensive school here and is organist to one of the meeting-houses; for so little fanaticism have now the Presbyterians of Belfast, that they have admitted organs into their places of worship. At no very distant period this would have been reckoned as high a profanation as to have erected a crucifix.

I was highly gratified with Mr. Bunting's execution on the piano-forte. Mr. Bunting is a large, jolly-looking man; that he should fail to be so is hardly possible, for Belfast concerts are never mere music meetings - they are always followed by a supper and store of wine and punch.

Mr. Bunting is accused of being at times capricious, and unwilling to gratify curiosity. But musicians, poets and ladies have ever been privileged to be so.

He has an extensive school here and is organist to one of the meeting-houses; for so little fanaticism have now the Presbyterians of Belfast, that they have admitted organs into their places of worship. At no very distant period this would have been reckoned as high a profanation as to have erected a crucifix.

I was highly gratified with Mr. Bunting's execution on the piano-forte. Mr. Bunting is a large, jolly-looking man; that he should fail to be so is hardly possible, for Belfast concerts are never mere music meetings - they are always followed by a supper and store of wine and punch.

Mr. Bunting is accused of being at times capricious, and unwilling to gratify curiosity. But musicians, poets and ladies have ever been privileged to be so.

J. Gamble, A View of society and manners in the North of Ireland in the summer and autumn of 1812, etc. London, 1813. Recommended reading!

Left: Edward Bunting, that "large, jolly-looking man."

Engraving attributed to William Brocas Jnr, and "most respectfully" dedicated "to the Harp Societies of Dublin and Belfast by their Obedient Servant James Sidebotham" of Lower Sackville Street, Dublin, 01 September 1811. See another version from the National Library of Ireland here.

Engraving attributed to William Brocas Jnr, and "most respectfully" dedicated "to the Harp Societies of Dublin and Belfast by their Obedient Servant James Sidebotham" of Lower Sackville Street, Dublin, 01 September 1811. See another version from the National Library of Ireland here.

In 1813,

that capricious and jolly-looking man organised a Belfast Music Festival which

began in the Theatre on 19 October and ended in his Rosemary Street

church four days later: a bargain offered as five concerts for two

guineas with a benefit concert for Mr. Bunting himself at which he

played a Mozart piano concerto.

Not only was this Festival a unique event in the history of Belfast but it was the first time Handel's Messiah was given in anything like complete form in Belfast - and this, over 60 years after the first performance in Dublin.

Bunting was responsible for a wide range of classical music in Belfast - though strangely not the newly formed Anacreontic Society (1814) in which his brother John was a prime mover, presiding "at the piano-forte with delicacy and great judgement" (Saunders's News-Letter, Thursday 30 December 1819).

Contemporary music was reflected in the meetings of a party of amateurs who practised Haydn and Beethoven symphonies under Edward Bunting's direction. Apparently the Eroica symphony looked so ferocious that it was postponed by universal consent.

Not only was this Festival a unique event in the history of Belfast but it was the first time Handel's Messiah was given in anything like complete form in Belfast - and this, over 60 years after the first performance in Dublin.

Bunting was responsible for a wide range of classical music in Belfast - though strangely not the newly formed Anacreontic Society (1814) in which his brother John was a prime mover, presiding "at the piano-forte with delicacy and great judgement" (Saunders's News-Letter, Thursday 30 December 1819).

Contemporary music was reflected in the meetings of a party of amateurs who practised Haydn and Beethoven symphonies under Edward Bunting's direction. Apparently the Eroica symphony looked so ferocious that it was postponed by universal consent.

In 1817, Bunting parted company, not on the best of terms, with Belfast's Second Presbyterian Church and became the first-ever organist of the new Chapel of Ease, St George's Church, in High-street.

The PDF below details that sorry parting of the ways and also explores St George's first organ - built by Stephen White.

The PDF below details that sorry parting of the ways and also explores St George's first organ - built by Stephen White.

|

St George's Stephen White organ.pdf Size : 354.75 Kb Type : pdf |

Right: St George's Parish Church, Belfast, drawn by Horatio Nelson from Dublin and published by Hardy in 1837.

Along with Bunting's frequent travels to London, there had been at least one visit to more foreign fields.

George Petrie:

In 1815, he visited Paris, while the allied sovereigns

were there, after the Battle of Waterloo. On this occasion his portly,

well-fed English appearance procured him the honour of being harmlessly

blown up, by a mass of squibs and crackers being placed under him as he

was taking a doze on a seat in the Boulevard; the crowd of mischievous

Frenchmen who surrounded him followed up the explosion with roars of

laughter, and exclamations of 'Jean Bull'!

Here, too, he made intimacies with many of the most

eminent musicians, whom he no less delighted by the beauty of the Irish

airs, which he played for them. He surprised them by the assurance which

he gravely gave that the refined harmonies with which he accompanied

them were equally Irish, and contemporaneous with the airs themselves.

"Match me that", said Bunting, proudly, to the astonished Frenchmen, as,

slapping his thigh, to suit the action to the word, he rose from the

piano-forte, after delighting them with the performance of one of his

finest airs.

Led by his love for music and particularly of the organ, which was at all times his favourite instrument, he passed from France into Belgium where, from the organists of the great instruments at Antwerp and Haarlem, he acquired much knowledge, which it was our good fortune to have often heard him display on our own organ at St. Patrick's [Dublin].

Sketch of Bunting by Henry Griffiths, published by James McGlashan, Dublin University Magazine, January 1847.

Bunting's appearance was quite distinctive and Petrie describes his "somewhat English face" as symmetrical, manly, independent, full of intelligence and character.

Well, all that about independence was about to be changed.

Well, all that about independence was about to be changed.

Dublin Weekly Register, Saturday 25 September 1819, page 3

Marriage

In St. Peter’s Church, Edward Bunting, of Belfast, Esq. to Miss Mary Ann Chapman, of Leeson-street.

Note: St Peter’s was a Church of Ireland parish church in Aungier St., Dublin (built 1685, enlarged 1773, rebuilt in Gothic style 1867, demolished in 1983).

Marriage

In St. Peter’s Church, Edward Bunting, of Belfast, Esq. to Miss Mary Ann Chapman, of Leeson-street.

Note: St Peter’s was a Church of Ireland parish church in Aungier St., Dublin (built 1685, enlarged 1773, rebuilt in Gothic style 1867, demolished in 1983).

So, in 1819, at the tender age of 46, Bunting married Miss Mary Anne Chapman, daughter of the lady principal of a Belfast school. Just prior to the engagement, Mary Anne's mother took up a new post in Dublin. Mary Anne obviously wished to be near the family, for thither went the newly-weds.

Edward had to begin a whole new pattern of life. It surely seems likely that this was the point he would have given up his organist post at St George's, Belfast.

His eldest brother, Anthony, had been based in Dublin for many years and with this contact and his many Northern connections - not least the influential McCracken and Joy families - Edward soon established himself as a respected teacher and was eventually appointed organist of St. Stephen's Church.

There were other problems, not least a period of residence with mother-in-law.

Edward had to begin a whole new pattern of life. It surely seems likely that this was the point he would have given up his organist post at St George's, Belfast.

His eldest brother, Anthony, had been based in Dublin for many years and with this contact and his many Northern connections - not least the influential McCracken and Joy families - Edward soon established himself as a respected teacher and was eventually appointed organist of St. Stephen's Church.

There were other problems, not least a period of residence with mother-in-law.

Above: Mrs Edward Bunting, née Chapman, from Vol.IV of the Journal of the Irish Folk Song Society, "published for the first time by kind permission of Dr Lewis Macrory".

Right: a daguerreotype photograph of Bunting in his late 60s.

Right: a daguerreotype photograph of Bunting in his late 60s.

Charlotte Milligan Fox:

A problem was the fact that the newly-married couple,

elderly husband and young wife, at first resided with Mrs. Chapman.

Bunting had not known since his early childhood the loving rule of a mother. The rule of a mother-in-law would naturally have been all the more irksome, and he was a man who, by his own avowal, suffered from irritability of temper.

Bunting had not known since his early childhood the loving rule of a mother. The rule of a mother-in-law would naturally have been all the more irksome, and he was a man who, by his own avowal, suffered from irritability of temper.

After a brief experiment, the joint residency was soon abandoned.

An intimate glimpse into the happiness of his married life is provided by a letter to Mary Ann McCracken. It is dated 29 December 1820 when his heart was still tender with rejoicing over his first-born child and only son, little Anthony.

Bunting:

An intimate glimpse into the happiness of his married life is provided by a letter to Mary Ann McCracken. It is dated 29 December 1820 when his heart was still tender with rejoicing over his first-born child and only son, little Anthony.

Bunting:

My wife seems happy now to what she did during her

mother's superintendence of the household, in consequence of my altered

behaviour perhaps. My little darling son is grown handsome. All the

people are delighted with him.

There were three children of the marriage and that picture of happy family life is probably the reason why Bunting almost disappears from sight for the next fifteen years or so. Almost, but not quite.

Interestingly, Bunting's first organist job in Dublin, as already mentioned, was in St

Stephen's Church, on Mount Street Upper - a church popularly known as 'The

Pepper Canister' because of the shape of its spire. It's the formal

Church of Ireland chapel-of-ease for the parish of St Peter’s, Aungier

Street, the largest Church of Ireland parish in Dublin. Begun in 1821

and consecrated three years later, its architect was John Bowden, the

architect of St George’s, High Street, Belfast.

The

church’s website refers to the organ case ‘built in 1754 by John

Snetzler … designed for the Rotunda chapel, but was never erected there.

It is thought to have been the property of Lord Mornington, father of

the Duke of Wellington, who lived in the parish’.

When the organ was installed in St Stephen’s, c.1824, had it retained any of Snetzler’s pipework?

Might Stephen White have been involved in the rebuild?

LH pic: Dublin's 'Pepper Canister' Church.

Illustration from the Dublin Penny Journal, Vol.4, 26 September 1835, p.97.

The church’s website also lists 'Historical Parish Figures', including Stanford, Yeats and Thomas Davis.

Sadly, not a word about Edward Bunting, the church’s first organist.

Nonetheless, the Archdeacon of Dublin, John Torrens (1761-1851) clearly thought very highly of Bunting's abilities.

This is from a vestry meeting report from page 2 of The Pilot, Wednesday, 22 April 1829:

A sum of £40 was proposed to be voted to Mr. Bunting, organist of St. Stephens’s. A parishioner alleged, that this was entirely too little, and the meeting would no doubt have voted £20 in addition for the organist of a chapel of ease, and that with acclamations, if the Rev. Archdeacon had not intimated that Mr. Bunting has actually £60 but that he [Archdeacon Torrens] supplies £20 from his own purse. (Hear, hear.)

Which is all very confusing, given that that newspaper report was dated April 1829, and he was still the organist at St. Stephen's, despite the December 1827 letter quoted below, suggesting an appointment to St George's, Hardwicke Place! So Bunting was the first organist of St Stephen's (once again, with a new organ!) from 1824, but so far I have failed to find a finishing date there, nor a definite starting date for him at St George's. Indeed, did he ever take up that position?

Taking a step backwards for a moment, in 1825, Bunting had embarked on a new commercial enterprise. He was one of the four proprietors of the Dublin Harmonic Institution, a grandiose name for a business selling sheet music and selling and hiring out musical instruments. The PDF on the right is a transcript of the initial newspaper advertisement.

|

Bunting's business venture 1825.pdf Size : 200.241 Kb Type : pdf |

That advertisement appeared in the Dublin Morning Register on Wednesday 07 December 1825 (page 1) and in Saunders's News-Letter on Tuesday 29 November 1825 (page 3).

But something didn't work!

The announcement transcribed opposite appeared on page 2 of Saunders's News-Letter on Thursday 19 April 1827.

Note the name of one of the

partners - William Walsh, a pianist and organist in Dublin from at

least 1821. He resurfaces, somewhat surprisingly, in a few years' time

in a role where Bunting's name was expected to appear!

DUBLIN HARMONIC INSTITUTION,

13, WESTMORLAND-STREET.

13, WESTMORLAND-STREET.

----

DISSOLUTION OF PARTNERSHIP.

THE Partnership which heretofore subsisted under the firm of Edward Bunting, William Walsh, Samuel James Pigott, and John Frederick Sherwin, of the City of Dublin, Music and Musical Instrument Sellers and Publishers, is this day dissolved by mutual consent, so far as regards the said Edward Bunting and William Walsh.Dated this 26th day of March, 1827.

EDWARD BUNTING.

WILLIAM WALSH.

SAMUEL JAMES PIGOTT.

JOHN F. SHERWIN.

S. J. PIGOTT and JOHN F. SHERWIN beg to inform the Nobility, Gentry, their Friends and the Public, that the business of the DUBLIN HARMONIC INSTITUTION will be in future carried on by them, under the firm of PIGOTT and SHERWIN, and respectfully request that all debts due to the late firm of E. Bunting and Co. will be paid them, they being empowered to receive the same; and they embrace this opportunity of returning their grateful acknowledgments for the distinguished support their firm has received, and beg to say, they shall endeavour, by constant personal attention, and by an extensive and fashionable Stock of Music and Musical Instruments, to merit a continuance.WILLIAM WALSH.

SAMUEL JAMES PIGOTT.

JOHN F. SHERWIN.

18th April, 1827.

Meanwhile, on 27 December 1827, thanks to the

assistance of the Attorney-General, Henry Joy (a cousin of Mary Ann McCracken), it looked as if Bunting was about to be appointed organist to Dublin's fashionable St George's Church.

Bunting (from 28 Upper Baggot Street, Dublin, to Mary Ann McCracken):